The majority of new product development projects focus on time and budget. However, this focus can conflict with delivering the most commercially successful product.

There is often the perception that design effort should be minimised in order to reduce cost and shorten timescales. In reality, the true costs of bad design (such as warranty returns from unsatisfied customers) emerge later on in the product life cycle, and have the potential to cause irreparable damage to the brand image through customer frustration.

The following pages aim to demonstrate that an inclusive design approach results in better products with greater user satisfaction and greater commercial success whilst reducing product development risk.

On this page:

The OXO Good Grips product range demonstrates great user satisfaction leading to commercial success.

Understanding ageing populations

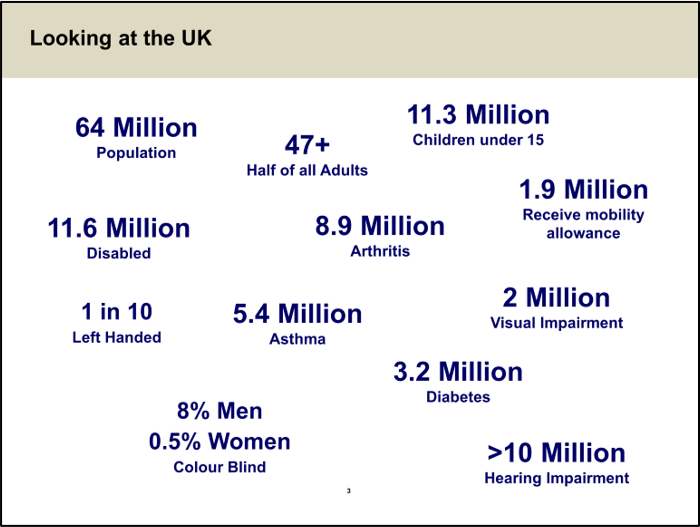

The demographics of the developed world are changing; longer life expectancies and a reduced birth rate are resulting in an increased proportion of older people within the adult population.

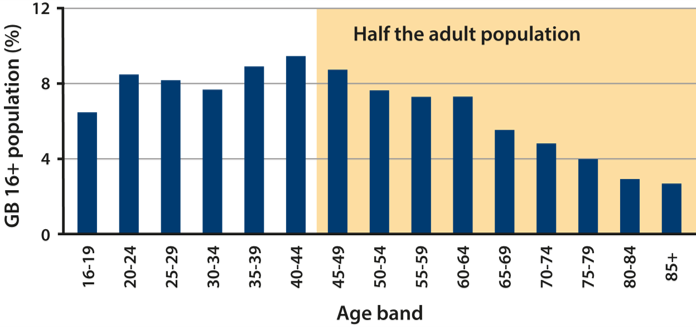

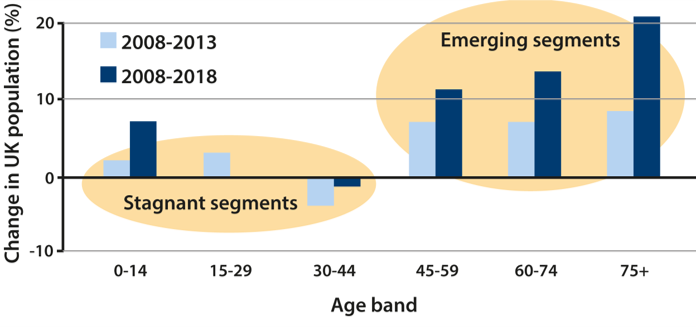

In 2008, half the UK adult population were aged over 44 (ONS, 2010a). Predicted population changes up to 2018 indicate that all age groups over 45 represent emerging market segments, with 75+ being the fastest-growing age group (ONS, 2010b).

Maintaining independent living for longer is therefore essential to maintaining a sustainable welfare system. The ageing population also presents a market opportunity for inclusive design.

The over 50s spent GBP 276 billion in 2008, making up around 44% of the total family spending in the UK (Age UK, 2010).

Further information

- A report by ONS (2010a): Pension trends, Chapter 2: Population change gives various statistics for the UK population.

- A report by ONS (2010b): Population Trends, No. 139, Spring 2010 gives further information about population demographics and trends.

- A press release from Age UK (2010): The ‘grey pound’ set to hit £100bn mark describes the importance of older market segments.

Designing for our future selves

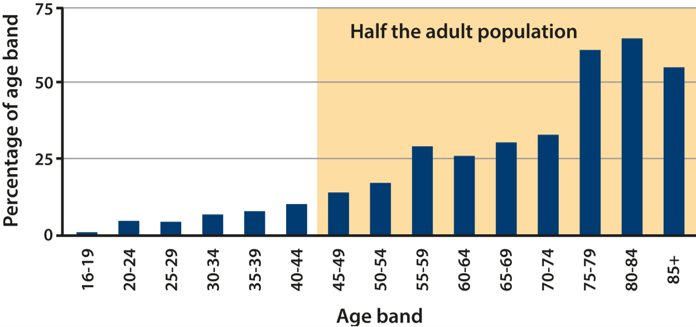

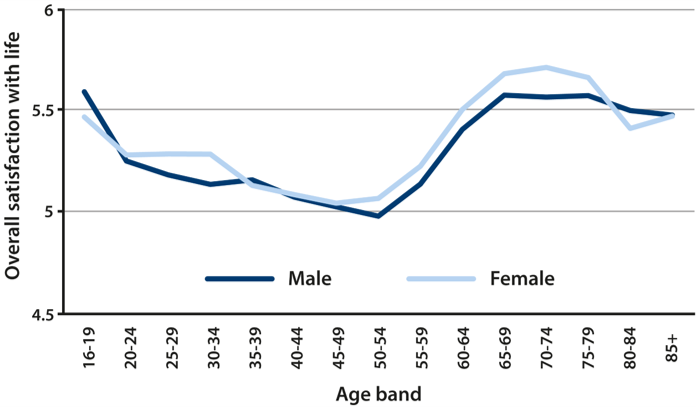

As people age, they often experience declining sensory, motor or cognitive capabilities. Yet increased age is also often associated with increasing satisfaction with life (see graphs below). Where previous generations accepted that capability loss and an inability to use products and services came hand in hand, the baby-boomer generation now approaching retirement are less likely to tolerate products that they cannot use.

“

For boomers, technology is contagious. And they don’t consider themselves technology dunces. Instead, they blame manufacturers for excessive complexity and poor instructions. ”

Typically, people are viewed as being either able-bodied or disabled, with products being designed for one category or the other. In fact capability varies continuously, and reducing the capability demands of a product results in more people being able to use the product and improves the user experience.

Percentage of people within each age band that have less than full ability, as defined within the Assessing demand page in the About users section of this website.

Further information

- A paper by Rogers (2009) for AARP: Boomers and technology: an extended conversation (pdf) examines how the boomer generation thinks about technology.

- Data from Understanding Society was used to construct the graph above about levels of satisfaction. The particular data was taken from Understanding Society: Wave 1, 2009-2010 [computer file]. 2nd Edition. Colchester, Essex: UK Data Archive [distributor], November 2011. SN: 6614.

The risk of bad design

Good design can happen by accident, but a rigorous inclusive design process mitigates business risk and ensures repeatable design success. In particular, understanding the diverse range of user needs can reduce the risk of undesirable and costly problems later in the product development lifecycle, such as:

- Excessive customer support costs

- A large proportion of no-fault found warranty returns

- Lawsuits

- Costly rectification work required close to, or after launch

- Customer dissatisfaction and brand degradation

The importance of adopting good, inclusive design principles early in the conceptual design stage is demonstrated by a report from the Design Council (1994), which found that changes after release cost 10,000 times more than changes made during conceptual design.

One costly example of insufficient accommodation of user diversity relates to the US Treasury. A court ruled that the Treasury discriminated against the blind and visually impaired by designing all denominations of currency in the same size and texture. Following this ruling, in 2011 the Treasury approved adding tactile features to US notes (Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 2011) at an estimated cost of $6.6 billion (ARINC, 2009). Subsequently, this proposal was changed to distributing free currency reader devices to eligible blind and visually impaired individuals, still at significant cost. The Business case materials contain many other examples of avoidable business costs.

Further information

- A Design Council (1994) report by Mynott et al. titled ‘Successful product development: Management case studies’ examines the cost of making changes at different stages of product development. Report available from: M90s Publications, DTI, Admail 528, London SW1W 8YT.

- A press release from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (2011): Meaningful Access Program.

- A report by ARINC (2009): Study to address options for Enabling the Blind and Visually Impaired Community to Denominate US Currency gives more details about proposed changes to the US currency.

The value of good design

Advancing technologies and digital interfaces mean that products can now offer more features at relatively low incremental cost. Indeed, companies can easily fall into the trap of competing in the ‘feature race’, trying to provide ever more features to keep one step ahead of the competition. However, increasing the number of features often hinders the usability of a device, due to the consequent increase in interface complexity and/or reduction in size of controls, symbols and text.

Philips (2010) found that the majority of Americans (63%) think technology companies don’t understand their needs when introducing new products. Indeed, 39% of Americans think these companies ‘fall in love with their own technologies’.

The impact of excessive complexity can be seen in results of a survey by Microsoft research. They asked users what they would like in the next version of Office, and found that 9 out of 10 people asked for something already in the product (extracted from Capossella, 2005). Other companies have delivered business success through a focus on simplicity, as described opposite.

Rather than just adding extra features, it is important to determine what functionality and features a product should include. This can provide an impetus for true product innovation and competitive advantage. An appropriate framework for achieving this is provided by inclusive design. In particular, it is helpful to set an appropriate target population and evaluate designs against the full set of inclusive design success criteria.

Further information

- A report by Philips (2010) : ‘The Philips Index: America’s Health & Well-being Report 2010’ examines various aspects of American’s health and well-being, including the role of technology.

- A keynote address by Capossela (2005) was part of Bill Gates’ keynote address at the Microsoft Professional Developers Conference 2005. This presented survey results on what users want in Microsoft Office.

Presenting the business case

An example Business case presentation has been created as a resource to help inclusive design practitioners or supporters to tell others about inclusive design. The general contents of the presentation are:

- Examples of the diversity of the world’s population

- Inclusive design as a response to diversity

- Why inclusive design is important from the perspective of general product and population trends/demographics

- The commercial imperative for inclusive design and an example of the success it can bring

The presentation can be downloaded from the Business case presentation page, where there is also an amateur video of the presentation being given.

Feedback

We would welcome your feedback on this page:

Privacy policy. If your feedback comments warrant follow-up communication, we will send you an email using the details you have provided. Feedback comments are anonymized and then stored on our file server. If you select the option to receive or contribute to the news bulletin, we will store your name and email address on our file server for the purposes of managing your subscription. You can unsubscribe and have your details deleted at any time, by using our Unsubscribe form. If you select the option to receive an activation code, we will store your name and email address on our fileserver indefinitely. This information will only be used to contact you for the specific purpose that you have indicated; it will not be shared. We use this personal information with your consent, which you can withdraw at any time.

Read more about how we use your personal data. Any e-mails that are sent or received are stored on our mail server for up to 24 months.